I'd given up on finding my 2nd great grandfather, Valentine's lineage after years of brick walls. His father finally showed up as Johann Wehrle from Baden-Wurttemburg and his mother as Theresa Schwab, also from Baden. Johann died in Germany, and as far as I can gather so did Theresa.

Using a Timeline generated by my Family Tree Maker software, Valentine's father died when he was two years of age, February 1831, one year before Valentine immigrated to America.

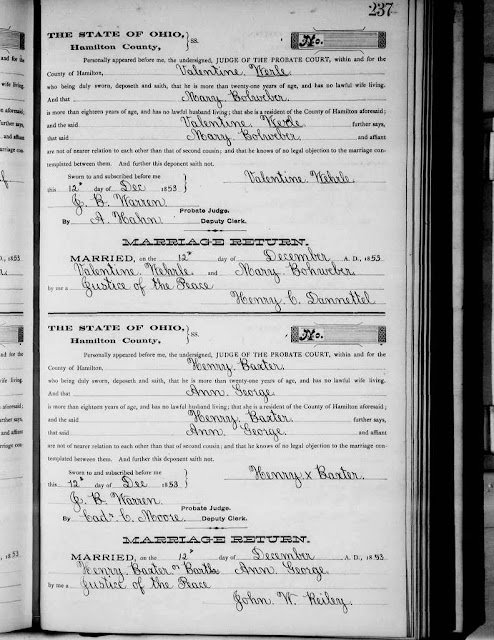

I haven't had such lineage success with Maria, Valentine's wife, my 2nd great grandmother, only that she was born in 1830 in "Bremen," as she reported early on in America but then changed to "Baden" in later years. Though my family has always referred to her as Maria, she's always been listed as Mary Ann, Mary A., or simply Mary on American documents. Her given name has appeared as Bohlweber, Bohweber, and Ballweber, none of which have unearthed any individuals. I find, however, that "Ballweaver" is a popular German name, offering up numerous connections. Thus far, I haven't found the right connection, but Ballweaver may be the correct maiden name of Maria.

Marriage (Son)

|

1888

|

||

59

|

Joseph L Wehrle

|

||

1891

|

Residence

|

1891

|

|

62

|

Cincinnati, OH

|

||

1899

|

Death

|

08 Nov 1899

|

|

71

|

Cincinnati,

Hamilton, Ohio

|

||

Port of Entry

Cincinnati in the 1850s was a still-young, tightly packed city. When the Germans began settling in the “Queen City of the West,” they came to a frontier town, and everyone knows life on the frontier was hard. They had come seeking a better life and found little or no work when they arrived. Worse, in a short time they became objects of hate. They were aliens, and like some other cities, Cincinnati residents believed these poor, beer-drinking immigrants would ruin their elite city.

Though

the Germans were highly instrumental in making Cincinnati what it is today,

first they had to fight a war in their new land to be accepted.

From France to the Queen of the South

Valentine Wehrle and Maria Ballweaver (or Bohweber) arrived in New Orleans on April 16, 1852, having boarded

passage in La Havre, France, on March 3, 1852. New Orleans was a common port

for Germans who chose to travel to La Havre to board ship.

_________________________________________________________________

Hamilton

County Ohio Citizenship Records 1837-1916

...

Hamilton County Ohio Citizenship Records, 1837-1916. ... Wehrle, Valentine,

26,

Baden, 3/3/1852, Havre, 4/16/1852,New Orleans. ...

libraries.uc.edu/.../collections/natdec/master.php?pageNum_Recordset1=961&totalRows_Recordset1=25523-16k-Cached

________________________________________________________________________________

Wehrle, Valentine Valentine Wehrle 26 Baden 3/3/1852 Havre 4/16/1852 New Orleans T 10/09/1854 F 6 117 F

Wehrle, Valentine Valentine Wehrle 26 Baden 3/3/1852 Havre 4/16/1852 New Orleans T 10/09/1854 F

________________________________________________________________________________

The ship is not named, and it may take longer than I want to keep researching this. The majority of these ships were American, so French ships may be missing, leaving an enormous gap in the records.

Germans settled in different locations depending upon when they arrived and where the best locations for economic opportunity were situated. When France, which had attempted to colonize Louisiana in the early eighteenth century with the help of Germans, assumed an important role in the cotton trade, German immigrants arrived in New Orleans and made their way up the Mississippi, Ohio, and Missouri rivers. ~ German Americans - History, Modern era, The first germans in america http://www.everyculture.com/multi/Du-Ha/German-Americans.html#ixzz1m6PbwInb

In

his 1829 book, Report of a Journey to the Western States, Gottfried Duden wrote

wonderful scenes of immigrant life in America.

One of the things important to Germans was their intellectual freedom,

and Duden praised America’s free lifestyle, intellectual and otherwise. His book was pivotal in persuading thousands

of Germans to emigrate.

The

failed German revolution in 1848 also stimulated emigration. Over the next ten

years over a million people left Germany and settled in the United States. Some

were the intellectual leaders of this rebellion, but most were impoverished

Germans who had lost confidence in its government's ability to solve the

country's economic problems.

Others

left because they feared constant political turmoil in Germany. One prosperous

innkeeper wrote after arriving in Wisconsin:

I would prefer the civilized, cultured, Germany to America if it were still in its former orderly condition, but as it has turned out recently, and with the threatening prospect for the future of religion and politics, I prefer America. Here I can live a more quiet, and undisturbed life...

Most

arrivals in America came from rural areas in Germany. These were often small

farmers and farm labourers who had suffered from advances in agricultural

technology during the 19th century. Many of these immigrants settled in

Wisconsin, where the soil and climate was similar to that in Germany. Of the

70,000 Germans who migrated to the Deep South, about 15,000 lived in New

Orleans. ~ http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAEgermany.htm

The voyage to the shores of New Orleans was not an easy one, and Valentine and Mary were aboard ship 44 days on their voyage from France to New Orleans. Illness, crowding, and less than sanitary conditions were suffered by the immigrants. A search of ships' manifests show a great many infants dying aboard the vessels.

|

| "From the Old to the New World" shows German emigrants boarding a steamer in Hamburg, to New York.Harper’s Weekly, (New York) November 7, 1874 |

When

Valentine and Maria arrived on the shores of New Orleans in 1852, believing they'd reached

the land of milk and honey, from reports passed on to German residents from

those already on America’s shores, they may have had a rude awakening. Assuming of course that the crowded, filthy

voyage from their homeland hadn't already given away some of what lie ahead.

Queen of the South:

Taken

from Queen of the South: New Orleans, 1853-1862, the Journal of Thomas K.

Wharton, edited by Samuel Wilson, Jr.,F.A.I.A., Patricia Brady, and Lynn D.

Adams

The nineteenth century was malodorous. After all, vehicles were horse or mule-drawn, regular bathing was uncommon, open gutters clogged with sewage lined the streets, and garbage was frequently left to fester. No wonder sweet-smelling plants — sweet olives, jasmine, gardenias, roses — were planted at the entrances to homes, not just for their beauty, but to counteract the pungent smells of the street…

Death and despair hung over New Orleans like a miasma that summer (1853). Longtime residents had acquired some degrees of immunity from the fever, but the sword of pestilence cut down unsuspecting natives and attacked areas of the countryside formerly believed safe from infection.

Unacclimated newcomers contracted the disease and died by the thousands. Apparently perfectly well one day, victims would suddenly be s t ruck with fever, jaundice, black vomit, and delirium, dying the following day. Others would linger for several days, unexplainably dying or surviving. Whole families died here, children there, and parentsSome of the diseases were brought over on the immigrant ships, like the great Irish famine and disease from 1845-52, resulting in approximately a million immigrants being transported to America.

elsewhere. So many children lost parents in 1853 that orphanages were opened to take care of them.

Yellow fever was one of the most dreaded diseases in port cities of the United States. Immigrants at all ports had to be examined by inspectors for signs of any infectious disease, and if any were found, the ship was quarantined. Typhoid epidemics flared in Philadelphia in 1837 and throughout the U.S. between 1861 and 1865. (http://genealogical-gleanings.com)

This

is the city – the Queen of the South – and the country, America, which was the new home to Valentine and Maria when they off-boarded at the Port of New Orleans.

Other

factors at the time in America added to the climate the Wehrles entered into. Slavery was popular, in the 1850s, in New Orleans and many other states, and thousands of slaves were

advertised in the newspapers—in the classified section. Sentiments of the German immigrants were

mixed. Many of the poor laborers were

against freedom for the slaves because of fear of losing jobs to them. Some were sympathetic to the cause and joined

the abolitionists.

I

have no way of knowing when or how Valentine and Maria traveled from New

Orleans to Cincinnati. The most common form

of transportation at the time, in the 1850s, was by river and following the

rivers on dirt roads by horse or horse and buggy, or of course on foot.

Steamboats

were in operation in the 1850s and were probably the most popular form of

travel, if one could afford it. By means

of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, one could board a steamship and travel

from

New Orleans to Cincinnati. The Erie

Canal provided for travelers to and from New York and other eastern ports.

Steam

locomotion had been invented but not to the extent that, even if someone could

afford the fare, had easy access to a train carrying him directly to his

destination. As Thomas Wharton journal

describes:

…People who didn’t own horses or carriages had to hire them from a livery stable or walk.

I

don’t know if Valentine owned a horse and carriage, or a horse and wagon, or if

he had money left over from crossing the Atlantic.

I

don’t know how long he and Maria stayed in New Orleans after April 1852, but I

do know that they were married in Hamilton County, Cincinnati, on December 12, 1853, a space of 20 months since arriving in the new country.

|

| Valentine and Mary's marriage 12 December 1853. This records shows Mary's given name as Bohweber. |

What were the reasons for moving to Indiana and then returning? A study of U.S. history may prove what drove the 1850s ancestors to make these decisions.

Next: Valentine and Marie. The Indiana Years.